The Good Samaritan

This sermon was first preached at our Sunday morning service on 10th July, following a week of political turmoil in the UK, triggered by the resignations of Rishi Sunak and Sajid Javid, the Chancellor of the Exchequer and the Health Secretary, which eventually led (a few days later) to the resignation of the Prime Minister, Boris Johnson.

The Gospel was a particularly famous passage, known as The Good Samaritan, and can be found in Luke 10:25-37. I hope you enjoy reading it.

It’s a cliché, but it’s very, very true: a week is a long time in politics. I don’t normally preach two weeks running, but I think it’s fair to say that more has changed in the world of politics since I last stood in this pulpit seven days ago than in the whole time since I preached before that, which was as far back as Easter Sunday!

No-one would have ever predicted this time a week ago that our government would have imploded to the extent that it has. I think roughly 40 ministerial positions have changed in that time – one of them; the education secretary; twice!

It’s comforting then, that at times of extraordinary change, some things remain constant. One of those comforting constants is the parable we heard this morning; the parable of the Good Samaritan.

|

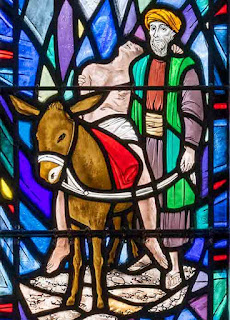

| The Good Samaritan window at Christ College, Canterbury, NZ |

I don’t know about you, but I’ve known this parable since early childhood. As a small boy, I was gifted some small religious books, each no bigger than a drinks coaster – ‘Little Fish Books’ I think they were called – by a great aunt. I remember reading this story in one of those books. I imagine many of us are in a similar position; the story is so familiar, most of us here could probably recite it by heart. It’s been a constant throughout our lives.

And the fact that it’s a constant makes it quite difficult to preach on! I half-toyed with the idea of retelling the story in a modern light, but I couldn’t find the right setting. I’d realised I’d got it wrong when I found myself starting off with “The Prime Minister was going down from Chequers to Downing Street, when he fell into the hands of his past catching up with him…” By the time I was replacing the priest and the Levite with the Chancellor and the Health Secretary, I wasn’t entirely sure this retelling was going in the appropriate direction…

So, what is there to say about this oh-so-familiar passage?

It’s always worth reminding ourselves of elements we might have forgotten. The first – and it’s oh so easy to forget this one today – is that Samaritans and Jews were enemies. Nowadays, our only real point of reference for Samaritans comes via this passage; the charitable group known for helping people at some of the lowest points of their lives is named after the Samaritan in our story. But in Jesus time, the Jewish people thought of the Samaritans as heretical, unclean and with great disdain. There were often attacks between the two groups. The closest comparison I can think of today is the relationship between the Israelis and the Palestinians, or the Ukrainian people and the Russians.

The other thing that is easy to forget is an explanation of the motivation of the priest and the Levite. These people, who were of the same religion and race as the wounded man – his natural neighbours – hurried on past him, without stopping. The reason for this was that their religion and position forbade them from helping. Touching this man, covered in blood and dirt, would have made them unclean. Not just physically, but spiritually. They were servants of God, and needed to remain pure and holy to serve in his holy temple. Touching this dying man would have rendered them unfit to enter into the presence of God.

But, as always with Jesus’ parables, there is always more to uncover as we delve deeper. Even with those parables that we have known for forty-odd years for me; perhaps even longer for you; even in those stories we can find they can still reveal to us new – and surprising – things about God and his kingdom.

Because that’s what Jesus’ parables were about. We like to think that this is a story about being kind to each other. But it’s not. Well, it is, but it’s not just about being kind.

It’s about the kingdom of God.

“How do I get into Heaven?”, asks the young lawyer at the start of our story.

“What do the scriptures says?”, replies Jesus.

And the young man responds – “love the Lord your God with all your heart, all your soul, all your strength, and all your mind. And love your neighbour as yourself.”

“Great answer!”, says Jesus.

And so, the young man asks a follow-on question. “Who is my neighbour?”

And Jesus tells the man the story of the good Samaritan (though he never calls it that) that we so know and love today. And then Jesus asks the man a question that ever so slightly shows a subtle different to the question the lawyer himself asked. “Who is my neighbour?”, asks the man at the start of the story. But Jesus – and I’m paraphrasing slightly here – asks at the end, “Who acted like a neighbour?”

Again, the lawyer answers correctly – he’s getting top marks today – the neighbour is the one who did something; who showed mercy. Yes, says Jesus – “go and do the same”.

But even though the lawyer got the answers right, the problem was, he got the questions wrong.

“Who is my neighbour?” asks the lawyer.

No, says Jesus. That’s the wrong question. Don’t try to work out who your neighbour is. The question you need to ask is, who can you be a neighbour to? Don’t try to work out which specific person or group of people is worthy of your love. Look for the opportunities to show love to whoever needs it.

That’s the difference between the Samaritan and the religious officials in our story. The Samaritan simply saw a person in need - it didn't matter who that person was; what mattered was that they were a person who needed help. And boy, did the Samaritan help! He helped in abundance. He doesn’t just bandage the wounds and send the man on his way; he stops his own journey, takes the man to an inn, pays for his board and lodgings and, not just that, tells the innkeeper that whatever he spends on him over the next days or weeks, he himself will pay when he returns. This is far beyond anything that was needed. It is not just mercy; it is grace.

This is the way of God’s kingdom – mercy and grace in abundance from a God – and have no doubt that the Samaritan in our story is a representation of God himself – who we have already declared our enemy. And still he shows compassion, shows mercy, shows grace and shows love to us.

This is how holy people behave, says Christ. Does your religion prevent you from helping people like the priest in this parable? Do your religious rules stop you from showing mercy to someone in need like the Levite? Then ditch them. Throw it all away as long as it means you can love like God does; in absolute abundance.

This is the way of God’s kingdom. Grace, mercy and love. All completely undeserved, and all completely free and all completely abundant for whoever - whoever - is in need of them.

And that, despite whatever is going on in the world of politics or current affairs, is always a constant.

Amen

Comments

Post a Comment